Almighty God, you strengthened St. Margaret of Antioch with faith and courage in the face of cruel persecution. Through her intercession, grant us the grace to stand firm in our own trials, trusting in your divine mercy. Fill our hearts with unwavering love for you and for all who suffer. May her example of steadfast purity inspire us to live with integrity and compassion, proclaiming the Gospel by our words and deeds. We ask this through Christ our Lord. Amen.

ST. MARGARET OF ANTIOCH

ST. MARGARET OF ANTIOCH

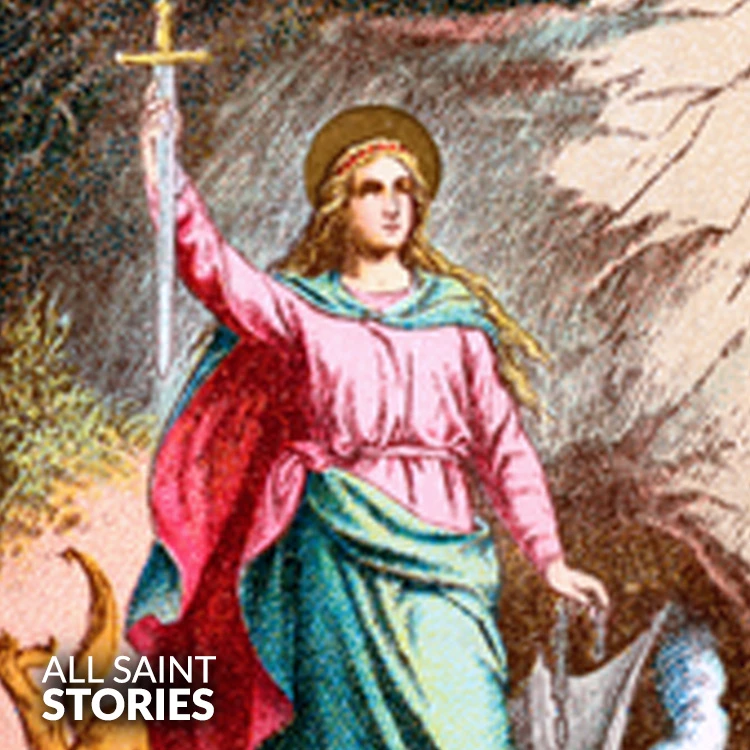

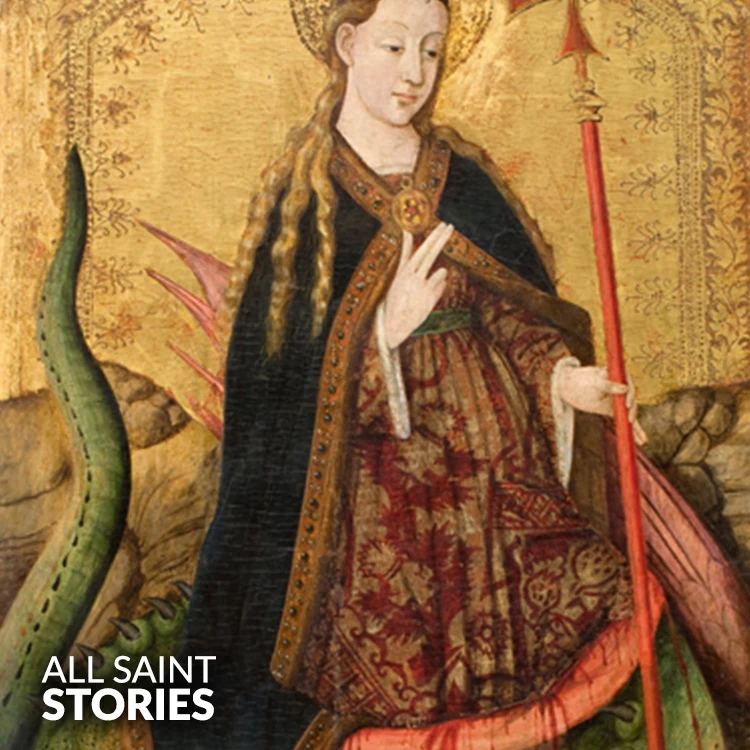

St. Margaret of Antioch was a young Christian virgin reputedly martyred under Roman persecution, traditionally placed in the early 4th century. Legends describe her steadfast refusal to renounce her faith, enduring various tortures before she was beheaded. Her story includes dramatic imagery of her defeating a dragon-like demon through prayer, symbolizing her victory over evil. Although historical details are scarce, she became one of the so-called “Fourteen Holy Helpers” in medieval devotion and remains a popular patron among women in labor. Her feast day is July 20, and she is often depicted with a dragon at her feet, illustrating her legendary spiritual triumph.

| t. Margaret of Antioch, also known in Eastern traditions as St. Marina, has been venerated since ancient times as a holy virgin and martyr. Despite the difficulty of verifying the precise historical facts of her life, her legend took deep root in Christian devotion, especially during the medieval period. Various accounts place her martyrdom during the persecution of Emperor Diocletian, around the year 304, when Christianity was still an outlawed faith in the Roman Empire. According to these narratives, Margaret was the daughter of a pagan priest in Antioch (in present-day Turkey or Syria, depending on the specific local traditions), though some sources locate her in the region of Pisidia. From an early age, she demonstrated curiosity and moral discipline, traits that led her to embrace the Christian faith in secret. |

Legends indicate that Margaret’s mother died shortly after her birth, leaving her to be nursed or raised by a Christian woman. In this adoptive home, she encountered the teachings of Christ, experiencing a deep conversion. By her adolescence, Margaret had grown into a striking figure known for her beauty. When her pagan father or, in other variants, a local Roman official sought to marry her off or force her to renounce Christianity, she refused. This act of defiance set the stage for a series of persecutions typical of martyrologies of the time. Although it is unclear how much of this is historically accurate, the accounts underscore the extreme risk of professing Christian beliefs under imperial edicts that demanded loyalty to pagan gods.

The famed legend that propelled Margaret to broad renown centers on her supposed battle with a dragon or demon. In captivity, she was threatened or attacked by a demonic manifestation which took the shape of a dragon. Tradition says the creature swallowed her whole, yet her faith in Christ delivered her from this dire predicament, either by miraculously escaping its belly or through invoking the sign of the cross. Medieval iconography depicts Margaret bursting forth from the beast, a vivid expression of spiritual triumph. While modern scholarship recognizes this as symbolic, reflecting biblical motifs of deliverance, medieval audiences took it as a testament to her power as an intercessor against evil, so much so that she became among the most beloved of the so-called Fourteen Holy Helpers—saints particularly invoked in times of grave need or affliction.

Ultimately, Margaret’s refusal to offer sacrifice to pagan gods led to her being tortured and finally sentenced to death by beheading. Early Christian sources give varying details on the manner of her trials—some describe scorching with hot irons, others mention being hung from racks—and her perseverance through these ordeals was attributed to direct help from God. Despite these terrors, she remained resolute, purportedly praying for her persecutors. Whether or not these exact events transpired, the essence of her story preserved in Christian lore is one of unwavering fidelity under lethal coercion.

Her popularity as a martyr soared in the Middle Ages when many localities built churches or shrines in her honor. Pilgrims sought her patronage for a variety of needs, but most notably, she became renowned as a protector of women in childbirth. This association might have partly derived from the symbol of her being “delivered” from the dragon, which in turn inspired pregnant women to pray for a safe delivery. Artwork from numerous regions across Europe depicts her with a dragon at her side, often pierced by a spear or crushed underfoot, signifying her conquest of sin, darkness, and fear.

Over time, Margaret’s cult spread widely, and many medieval knights, crusaders, and laypeople regarded her as a model of fortitude. Translations of her relics—though historically unverified—were reported in various places, with local legends claiming they possessed healing powers. During the centuries when plague and warfare repeatedly struck the populace, devotees turned to Margaret and other Holy Helpers with fervent supplications. She was frequently depicted alongside Saints Catherine of Alexandria and Barbara, forming a trio of virgin martyrs who exemplified intelligence, courage, and purity in the face of adversity.

In the East, under the name Marina, she held a similar status. Local traditions recount parallel narratives of miraculous escape from a beastly foe, underscoring the unity of Christian devotion that stretches across different liturgical practices and languages. Yet textual analysis suggests that the account of Margaret’s life, as circulated in the West, reached its mature form by the 9th or 10th century, gaining further embellishments through hagiographers who aimed to inspire the faithful with stories of saints whose prayers were believed to break the hold of demonic forces.

Despite the entanglement of legend and history, the Church’s longstanding recognition of Margaret as a martyr is evident from her listing in early martyrologies and her widespread commemoration on July 20. While modern reforms in the Roman Calendar might have reduced some local feasts or re-evaluated certain legendary accounts, she remains venerated in many places, particularly in Eastern Christianity, Anglican communities, and among certain Catholic devotions. Many parish churches named in her honor exist throughout Europe, notably in England, where she was revered during the Middle Ages. Even in regions as far as Latin America, devout families sometimes name daughters “Margaret” or “Margarita” in honor of her courageous example.

Culturally, her story taps into the theme of a young woman triumphing over adversity, unshaken by physical intimidation or societal pressure to abandon her faith. For those facing persecution or hostile environments, Margaret’s story provides a timeless symbol of hope. For expectant mothers, she remains a heavenly patron, representing the possibility of safe passage through painful circumstances. Artists have often used her iconography to portray the inherent spiritual battle each believer wages against evil, with the dragon signifying the underlying forces that threaten moral integrity.

In summation, while documentation about her actual life is sparse, the significance of St. Margaret (or St. Marina) of Antioch in the Christian imagination remains profound. The persistent devotion to her across centuries underscores how her narrative resonates with core Christian values: faithfulness unto death, divine deliverance from darkness, and unwavering trust in God amid formidable trials. Even as historical scholars view certain elements of her legend as symbolic, the Church’s traditions continue to present her as an example of unbreakable resolve. Her feast day celebration each July 20 invites the faithful to reflect on themes of endurance and divine support, whether in the pangs of childbirth, the challenge of demonic temptations, or broader struggles of conscience and belief.

Video Not Found

The information on this website is compiled from various trusted sources. While we aim for accuracy, some details may be incomplete or contain discrepancies.

If you notice any errors or have additional information about this saint, please use the form on the left to share your suggestions. Your input helps us improve and maintain reliable content for everyone.

All submissions are reviewed carefully, and your personal details will remain confidential. Thank you for contributing to the accuracy and value of this resource.

Credits & Acknowledgments

- Anudina Visudhar (Malayalam) – Life of Saints for Everyday

by Msgr. Thomas Moothedan, M.A., D.D. - Saint Companions for Each Day

by A. J. M. Mausolfe & J. K. Mausolfe - US Catholic (Faith in Real Life) – Informational articles

- Wikipedia – General reference content and images

- Anastpaul.com – Saint images and reflections

- Pravachaka Sabdam (Malayalam) – Saint-related content and insights

We sincerely thank these authors and platforms for their valuable contributions. If we have unintentionally missed any attribution, please notify us, and we will make the correction promptly.

If you have any suggestion about ST. MARGARET OF ANTIOCH

Your suggestion will help improve the information about this saint. Your details will not be disclosed anywhere.

© 2026 Copyright @ www.allsaintstories.com

English

English

Italian

Italian

French

French

Spanish

Spanish

Malayalam

Malayalam

Russian

Russian

Korean

Korean

Sinhala

Sinhala

Japanese

Japanese

Arabic

Arabic

Portuguese

Portuguese

Bantu

Bantu

Greek

Greek

German

German

Dutch

Dutch

Filipino

Filipino